Semi-trivial interaction and data mining: Black Mirror Bandersnatch and the tragedy of Netflix

[Contains format-specific but not content-specific spoilers]

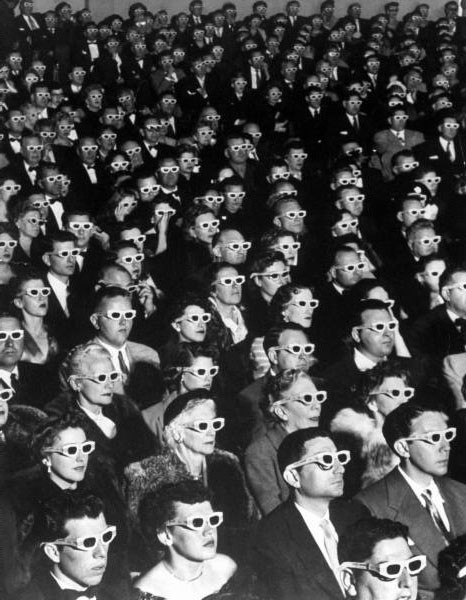

From the ’83 edition cover of Guy Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle”

The popular dystopic TV series franchise Black Mirror, recently acquired by Netflix, put out a chose-your-own-adventure type episode on December 28 2018.

For Black Mirror to experiment with such a format, and for it to be made available in the primetime of the Christmas holidays, is perhaps worth taking a closer look at. It would be harsh and perhaps unfair to judge a first experimental approach targeted to popular audiences in terms of its content, in comparison to the rich tradition of interactive media. However, we do have to talk about its format, and the tradition it implicitly carries along.

To be fair, Netflix remained quite secretive about it, even though the press published various leaks since earlier this year. Wikipedia reports that in October Bloomberg published that Netflix was working on interactive titles, though Netflix still didn’t officially comment on the subject, until the episode’s release. Even the trailer was only published one day before. Perhaps “chose your own adventure” was never suggested as a format, but the term “interactive” that was mostly used, cannot but betray a relevance -besides the episode’s content.

Don’t get me wrong, I am all for popular approaches to experimental formats. And it if takes such a TV franchise and a commercial giant to acquaint a larger audience to interactive stories, and perhaps revive an interest into other such literature like interactive books, hypertext fiction and computer game interactive fiction, and even contribute to it, so be it. Why not?

But the thing we see here, I would like to suggest, is the opposite. This -hopefully only first- interactive episode fails in its interactiveness. And the reason for that I would additionally argue, is Netflix. For the sake of the story, Netflix had the additional task of developing their own branch management system and make it technically possible to stream such content seamlessly without interruptions -while cuts might appear clumsy, technically it works quite well and there is no buffering time.

Bandersnatch and the Netflix Experience

The problem with Netflix is its own exaggeration of the rhetoric of the seamlessness experience, the Netflix experience, which fails Bandersnatch to be regarded as an actual interactive experience. The UX championed by Netflix, doesn’t need you to do much. As soon as the ending credits kick in, the film you are supposed to watch is minimised to a thumbnail and put to the corner, for further film suggestions to take over the screen real-estate. Series episodes automatically advance, cutting through the ending credits, giving you just a few seconds to catch a breath in between. On their website, film trailers will trigger automatically with full blown sound as soon as you even hover-over a film poster. Netflix’s adopted motto seems to be “you will never be bored.” You are promised practically infinite quality material to chose from. The credits are unimportant. It’s just the entertainment part. Everything is reduced to spectacle, as was once said. Practically, Netflix apps and websites don’t want to leave you unattended without stimuli. Not even for a moment to think. Netflix is also happy to play minimised, or in the background. Besides, it’s Netflix which established binge-watching as a popular term, and encouraged it by dropping whole-season-episodes on a single day. As it has been written also for many other media, Netflix is in the market for your attention, at all time-scales. And for that, its strategy apparently is to keep you laid-back and entertained with a seamless flow of content at all costs. Given its popularity, we cannot but assume that this UX philosophy apparently works and it’s at least tolerated by its users. [Besides, without such tradition, and with so many things going on nowadays, it doesn’t seem to make much sense to complain about the suggested user experience of a popular net streaming service… And additionally who should one address for that?]

And here is where this rhetoric comes to clash against the premise of this Black Mirror episode. Having interactive parts means having to have an interruption of the plot, in order for the viewer-player to make a decision. The content has to pause and the film has to be rather idle to await and facilitate the decision. Incidentally, this is the crucial moment that defines this episode to belong to an “interactive media” genre. “Choose your own adventure” is called like this because You, the player actually choose your own adventure. You are the source of narrative, which becomes a personal story. Espen Aarseth, in his acclaimed book “Cybertext” introduced the term “ergodic literature” to describe such media. From the first page of his introduction, Aarseth offers a crucial definition:

In ergodic literature, nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text. If ergodic literature is to make sense as a concept, there must also be nonergodic literature, where the effort to traverse the text is trivial, with no extranoematic responsibilities placed on the reader except (for example) eye movement and the periodic or arbitrary turning of pages.

In interactive media you don’t just follow the pages or passively sit through a film. At some point you have to stop reading/watching/consuming and make a decision, essentially changing the course of the story. It won’t go anywhere otherwise. This selection is not trivial, at least not in the same sense as the act of reading. It is of a completely different nature to a passive consumption of the medium, as it empowers the “reader” to assist forming the content alongside the actual author. Therefore the crucial act and fact of choice, has to be treated both as serious and sacred.

I watched Bandersnatch with 4 friends who were not particularly aware of the format -not to say that I am particularly relevant. However, everybody knew that it was somewhat special in terms of interaction. When the first selection came about, another element appeared that it would later prove destructive. The selection pane had a timer bar. It’s a horizontal thin line, dwindling towards the center, above the clickable options options, in the lower black space and just below the widescreen video frame.

While the first selection that probably served as an introduction to the general scheme was rather trivial, later ones were not. We had to take radical, and radically different decisions in what seemed like a race against the clock. But it wasn’t just the time limitation, it’s also its dramatisation. I don’t know if an hourglass or any other representation would be any different, but the timer bar running out from both far reaches of the screen to the center, and just above the options you have to read and reason, introduced an additional element of stress. Eventually, the moment of selection seemed so rushed and insignificant, that did not allow us to meaningfully consider the options we were given. Without proper time to think, following along a rhetoric of snap decisions, we didn’t seem to feel that we were either empowered or in control of the story. We were merely interrupted in order to quasi-casually click and resume the film.

Perhaps it is yet another stunt of Black Mirror’s unconventional writing, that wanted to have another element of tension, in having a dramatic countdown bar, along all of the technical effort and extra gimmicks that were jam-packed into it, like the instances of the 4th wall fragility. But that wouldn’t be my first bet.

Additional to that, is the fact that Bandersnatch does not have harsh or dead ends, or any equivalent of a game over. True to its values, the “branching system” of Netflix manages to cycle through transitions rather seamlessly, not only when one choses, but also when a telos comes, as there is no distinction between the two. The branching system will bring you back and restart from an earlier point if needed, without a sign or pause to give time to reflect on what happened. It thus fails to communicate where each branch ends, along with any signification of the actual structure of the story or our apparent causal relation to its teleology. There is no apparent cost to choosing any option. Not that they don’t alter the story, but if there are no consequences to them, as the branching engine is happy to take you forth and back back until you exhaust the content -which is the only thing that Netflix seems to understand. You don’t have to restart, go back and traverse again.

By Aarseth, interactive content presupposes effort -“work”- and Netflix, as the epitome of past-time laid back entertainment, seems to be come too soft on its audiences. No pain no gain is the motto here.

In one sitting we did 7 of 9 reported endings without a harsh end or “game over” in between. Asking my fellow co-viewers how many endings we watched, the answers ranged from 2-4 (about 30-60% of 7). Only in the last couple of selection panes, a tiny button appeared at the top right corner prompting if we want to opt out, suggesting that it’s possible and acceptable to put an end to it. However, its position and similitude to common Netflix -skip-intro and watch next- popups, rather than the interactive options that are in the bottom of the screen and are of a different graphic representation, kept us rather confused on where and which elements are diegetic and which not.

The question in the end was “did you like the film”? which betrays two problems. First, it’s not supposed to be a film. Second, it should have been our film -we should have felt like we had something to do with it. In these terms, Bandersnatch is more of a videogame-action type of fast paced decisions, instead of of a proper interactive adventure one.

Eventually, there wasn’t much time to honour the premise of interaction in a meaningful sense, as the function of the selection as well as of the audience, and contrary to Aarseth’s theory, were trivialised. Additionally, the whole experience seems to want to exhaust as much of the video content as possible, rather than get you involved to make sense and meaningfully perform it. This is what I would like to suggest the tragedy of this Netflix episode, making something fundamentally non-trivial, trivial enough.

Is this episode good? I would rather say yes. Is it interactive? Yes, you have to click every now and then. Is it a chose-your-own adventure? No. It doesn’t offer time for meaningful ergodic play. It makes you lean forward, as Peter Rubin of Wired writes, but not enough, I am tempted to say. Not enough to say that the audience was given the proper agency and be incorporated to the story mechanism.

Data Mined Futures

Additionally, what can be only speculated from Netflix’s deep dive to a new format during Christmas holidays primetime, is that now on, it’s not only our film preferences that are recorded, our in-film choices are being recorded too. Bandersnatch is neither a book nor hypertext, not even a DVD. The medium of Bandersnatch is Live-Streaming through a platform gradually developed on the premise that it can [reverse] engineer your taste to suggest what you should watch. And that’s not an easy trivial feat -neither cheap. Like our preferences, our choices are recorded bound to be processed and be output back as content. Jessi Damiani of the Verge highlights the product placement wrapped in the first selection pane of Bandersnatch, as a prologue to a potential mass and tailor-made advertisement that Netflix could eventually embark upon.

But it’s not only that. Given time, both theirs and ours, we can only anticipate an over-engineering both of our own digital profiles, as well as of such interactive content. As Damiani continues:

Those choices offer unprecedented insight about what Netflix’s subscribers want out of a story and what choices they most want to see characters take. User-generated data has already guided Netflix’s creative decision-making when it comes to marketing original movies like Bright. Bandersnatch represents a new form of data mining that gives Netflix richer, more specific audience information than it’s ever had before.

The volume and quality of fine tuned data that Netflix will mine if it continues to pursue interactive films will be unprecedented -especially if it does it well. Imagine having millions of entries on sequences of binary options. This is precisely the type of data that machine learning algorithms want and can work with. It won’t be long until we have algorithmically cooked interactive stories, or even generic films for that matter.

Since what Bandersnatch intends to be is not a film, but content belonging to the electronic literature tradition, and the larger videogame genre, it would make sense to see it through that scope. The two relevant late advancements coming from this genre are gamification and casual gaming, that is worth to consider against Netflix’s new endeavour. Multiple scholars and practitioners have been vocal about the predatory aspects of these practices targeted mainly to videogame-illiterate groups. Between them Ian Bogost wrote of gamification as “bullshit” and “exploitationwear.” Videogame designer Jonathan Blow discussed casual games like Farmville, that are engineered on a hormonal level to get their users hooked and “feeling shitty” while they are away from the game -no wonder how such companies built their empires with innocent looking free games, that just allow “micro-transactions.”

Now consider Netflix. A multi-billion worth of what started as a centralised real-time film-streaming provider, and has grown to one of the most recognisable household names with an international user base of some 137 million (2018), able to produce its own -also international- film titles and series. If Netflix sets their mind on employing schemes such as the ones criticised by Bogost and Blow for the production of their films, no doubt they have the resources to perfect them.

I would not be concerned with Netflix doing product placement -even though it already proved that it can slip brands in under the radar. I would be concerned if it embarks in computational and algorithmic script-writing, employing the narrative medium it just “invented” and essentially its viewers to tune it. And it will. If it continues, it won’t just ignore the selection-data it gathers on the way, it will put them to use. As the sole currency of Netflix is viewership, the sole purpose of these algorithms will be to glue you on the couch – clicks optional. And if the options of this episode weren’t violent enough, prepare to be fundamentally ethically torn.

Libidinal economy – libidinal “art.”

Graz, Austria, January 3 2019.

Notes:

1. Watching an interactive film in a 5-piece is not ideal, and can additionally be argued that it requires more time to make collective decisions that exaggerated my former claims about the timer duration, which is agreeable. Though since Netflix appeals to popular and family audiences, and does not suggest individual viewing particularly for content such as the one described above, I believe it is valid to suggest that collective audiences are not discouraged, though practically the selection timer does not really facilitate collective decision-making -either.

2. It could be the case that the selection timer bar renews and restarts after its expiration. We never tried to let it expire, so I don’t know, and since I am concerned with the rhetoric of the interface, I am not concerned with that case.

Aarseth, Espen J. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Bogost, Ian. “Persuasive Games: Exploitationware.” Gamasutra, 2011.

Bogost, Ian. “‘Gamification Is Bullshit.’” The Atlantic, August 9, 2011.

Bogost, Ian. “The Rhetoric of Video Games.” In The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning, edited by Katie Salen, 117–140, 2008.

Frasca, Gonzalo. “Simulation versus Narrative. Introduction to Ludology.” Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf and Stephen Perrella. The Video Game Theory Reader, 2003, 221–235.

Fernandez-Vara, Clara. “Labyrinth and Maze.” Edited by Friedrich von Borries, Steffen P. Walz, and Matthias Bottger. Space Time Play, 2007, 74–77.

Gazzard, Alison. “Routes through Gamespace: Maze Paths and Tracks in Videogames.” In Ludotopia II, Vol. 1. Manchester, UK: The University of Salford, 2011.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media. 2 edition. London: Routledge, 2001.

CreativeMornings HQ. Jonathan Blow: Game Design: The Medium Is the Message. CreativeMornings, Portland, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxFzf6yIfcc.

rubbermuck. Jonathan Blow: Video Games and the Human Condition. Rice University, Houston, Texas, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqFu5O-oPmU.

pmilat. Mark Fisher : The Slow Cancellation Of The Future. Mama, Zagreb, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCgkLICTskQ.